- limited 25th Anniversary Edition -

- limited 25th Anniversary Edition -

| Disclaimer Images used, herein, are owned by the individual copyright holders and are presented for review and promotional purposes only. |

Ausschlussklausel Hier dargestellte Bilder sind Eigentum der jeweiligen Rechteinhaber. Sie sind ausschließlich zum Zwecke der Rezension und der Promotion dargestellt. |

|

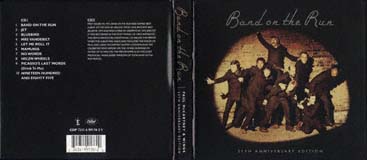

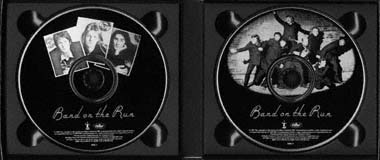

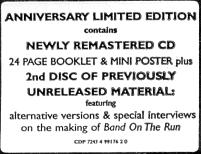

cardboard box - front and back  cardboard box - inner side with discs |

| Release dates and order numbers:

|

|

"THIS ANNIVERSARY EDITION OF BAND ON THE RUN

IS DEDICATED TO MY BEAUTIFUL LINDA AND HER INDOMITABLE SPIRIT"

PAUL McCARTNEY

|

|

|

|

Notes from the 24-page booklet:

By 1973 it was clear that Paul McCartney was continuing the fast-track pace of record releases that the Beatles had established the previous decade. Unveiled that December, Band On The Run arrived some three and a half years after the Beatles' final album and yet it was already Paul's fifth - and his third with Wings.

What is more, in the same period, Wings had also issued several singles not on those albums, cut enough additional tracks to fill a further platter or two, toured three times in less than two years, made a TV special and numerous promo videos and taken a band holiday. And all this while the McCartneys were raising a young family.

And yet ... and yet ... of all these early, hectic projects Band On The Run is the album that really shouldn't have worked; it is an album, indeed, that remains as good a proof as any that art can indeed triumph over adversity - Big Time. The circumstances of the recording of Band On The Run were such that the project seemed to have a mighty hex hanging over it. Instead, it was an achievement that smashed sales records and re-established Paul McCartney's artistic credentials with the record-buying public.

Wings toured Britain in the spring/summer of 1973 in support of their second album Red Rose Speedway and its single, 'My Love'. These were the band's first shows for the British general public, following their excursions a year earlier when the McCartneys and their new musician friends piled into a van and famously turned up at universities and asked if they could play for the students at 50p a throw. Wings' 1973 tour followed a more traditional route, though: 15 theatre dates in May and four more in July when the band returned to the road to plug their Bond-theme single 'Live And Let Die'. (Fantastically, this reached number 007 on the NME chart) Then, post-tour, the McCartneys drove up to their Scottish retreat, where, within days, Paul and Linda began writing the songs for Band On The Run.

As ever, they drew inspiration for these new songs from a wide variety of sources, and though Band On The Run was largely recorded beyond the UK, its lyrical influences remain firmly British, with references to plastic macs, suffragettes, registered charities, blinking lights and the need for 'a pint a day'. 'Down in the jungle, living in a tent' was a catchphrase of the British music-hall comic Charlie Chester, 'Jet' was the name of one of the family's labrador puppies in London (recalling 'Martha My Dear', this was the second time Paul had tided a song after a dog), and 'Helen Wheels'- the McCartneys' nickname for their Land Rover - even cited Glasgow, Carlisle, Kendal, Liverpool and Birmingham as it journeyed down the M6 motorway.

But there was also an internationalism abroad, viz the mentions of the desert world, the county judge,Vanderbilt, Washington and UCLA. Paul derived the song title 'Mamunia' from a house name-plate he saw in Marrakesh during a Wings holiday earlier in 1973 (in Arabic, the word means a safe haven), and 'Picasso's Last Words' was written in Jamaica in late April 1973, in circumstances that would be re-told in a most entertaining fashion. It was composed at the behest of Dustin Hoffman, who invited Paul to write a song on the spur of the moment and handed him a copy of Time magazine as inspiration, pointing to an article titled 'Pablo Picasso's Last Days and Final journey'.

Although Paul had recorded McCartney, solo, at home and in London studios, and he and Linda had taped Ram in New York and Los Angeles just a few months later, Wings had latterly established a pattern of recording in London, principally at the EMI Studios on Abbey Road. Being an international company, however, EMI had studio operations in a number of countries; seeking somewhere new to work, by way of a change from Abbey Road, Paul asked EMI to let him know the cities where Wings could record in the company's own studios.The list included Bombay, Rio de Janeiro, Peking and Lagos.

Lagos!

For Paul, the word conjured up images of lazy days, hazy days, hot tropical days, days of ceaseless music and buzzy rhythms on the vest coast of Africa. He envisaged 'lying on the beach all day, doing nothing and recordi at night'.

But as he noted later, drily, 'It didn't turn out quite like that.'

It was a cavalier decision. The McCartneys didn't know that Nigeria was run by a gun-happy military government, the result of a coup seven years earlier. They didn't know that, while Nigeria was a member of the British Commonwealth, the first thing they'd see at the airport was men wielding machine guns, that lepers walked the streets, that even the capital city had open drainage, that few things functioned there - officially or unofficially - without generous parking. Perhaps they also didn't know that they would be arriving in Nigeria towards the end of its rainy season, when the heat and humidity were at their most intolerable for Westerners and the Lagos rain fell in monsoon-like torrents. They were almost certainly unaware that, before leaving England, they'd have to be given inoculation after inoculation to prevent the risk of catching cholera, typhoid, polio and sundry other ghastlies.

Whatever, at the beginning of August 1973, just over a week before they were due to fly out Paul and Linda invited Wingsmen Denny Laine, Henry McCullough and Denny Seiwell to Scotland, where they could routine the new songs together. Straight away, though, it was clear that relations within the band were strained. Rumours that Henry, the lead guitarist, was planning to quit had hung over the British tour; now he quickly fell into a dispute with Paul over a guitar passage that he declined to play. Each knew that compromise was the best solution but neither was prepared to budge - McCullough walked out and then phoned to announce his resignation.

Then, on 8 August, the evening before departure, drummer Denny Seiwell also withdrew, telling Paul by phone that they should go on without him. Wings had been reduced from a quintet to a trio within the space of a few days.

Never mind, Paul declared, he'd worked without these guys before and he could do so again. He had drummed on stage a few times, and on the McCartney album, so now he would pick up the sticks once more. Moreover, he and rhythm guitarist Denny Laine could easily share Henry's lead parts. And at least the recording process itself would be in safe hands, for Paul had invited Geoff Emerick to engineer the sessions. Geoff had been a good friend for some seven years, his talents having helped the Beatles to shape no lesser albums than Revolver, Sgt Pepper and Abbey Road.

Emerick. certainly was ill-prepared for working in the Nigerian studio.The EMI building, situated in Wharf Road in the suburb of Apapa, was distinctly ramshackle. The control desk was faulty and there was just one tape machine, a Studer eight- track which, in all likelihood, was a past-its-prime outcast from London.The studio was not equipped with the proper acoustic screens necessary for sound separation, and it was only after a search that the microphones were discovered in a cardboard box in a cupboard. At the rear of the studio, through a door that was thankfully soundproofed, EMI ran a record pressing-plant, where staff bustled over noisy machinery and stuffed discs into sleeves. On the first day, Geoff Emerick was introduced to the studio manager, Monday, and a friendly chap, charmingly named Innocence, who would man the tape machine for him. There was little security at the studio, though - certainly no sign of a commissionaire or security guard - but Wings' discreet presence in Lagos meant that few people stopped by the studio to seek autographs.

Wings rented a couple of houses near to the airport, at lkeja, an hour's drive from the studio. Paul, Linda and their children (three, at this point) stayed in one; Denny Laine, Geoff Emerick and Wings' two roadies resided in the other. But Geoff took a strong dislike towards the local creepy-crawly population - the spiders and lizards in particular - and after Denny kindly put some dead spiders in his bed, as a 'surprise', and another occasion when he woke up one morning to see an iguana flicking its tongue at him through the window, he opted to stay in a hotel instead.

A daily pattern was quickly established. Paul wanted to swim, so temporary membership of a local country club was arranged - the manager said that they could join if Paul signed a photograph of the Beatles that was hanging on one of the walls. Mornings were mostly spent here, followed by a leisurely lunch.Then each afternoon at around 3 the team were driven to the recording studio, where work proceeded until 10pm, although on a few occasions it continued until 4 or 5 the following morning. No recording was done at weekends, when tourism and relaxation were the top priorities. One day was spent with Chief Abiora, who invited everyone to his country house in Dahomey, and another was spent attending a party on a nearby island.

The recording of most tracks began with Paul playing drums and Denny the rhythm guitar, laying down the sones foundation. From here, by a process of layering, and with Linda adding keyboards, each song slowly took shape. No mean lead guitarist, Paul played most of these parts. Losing the two band members had galvanised Paul, Linda and Denny, fostering a 'we'll show yer' attitude and a survival instinct that might not otherwise have been present.

But while the sessions ran smoothly, the technical problems notwithstanding, the McCartneys experienced other local difficulties. Although they had been warned not to walk anywhere, Paul and Linda considered that little harm would come to them if they did, but strolling back from Denny Laine's villa one evening they became aware that they were being tailed by a car. In a flash, five young men jumped out of the vehicle and robbed them at knifepoint, the shiny steel blade being pointed at Paul's throat while the possessions were handed over and Linda pleaded with the men not to murder her husband. The muggers took every valuable item the McCartneys were carrying - camera, jewellery, money and even the cassettes on to which Paul had recorded demos of the songs he planned to record.

If I ever get out of here, thought of giving it all away ...The robbery was deeply distressing and it was only a small comfort for Paul and Linda to be told later, that, had they been black, they would almost certainly have been killed, lest they identify their assailants. White people, it was reckoned, are often unable to distinguish black faces, so there was little likelihood of this happening.

On another worrying occasion, Paul collapsed in the recording studio, unable to breath and complaining of pains. Desperate for some fresh air, he staggered outside, only to pant in the fetid tropical atmosphere. Linda suspected that he was having a heart attack and urgent medical assistance was sought. The doctor ordered rest.

Emotions were becoming raw. On an evening visit to The African Shrine, a club owned by the local Afrobeat star and political activist Fela Ransome-Kuti, Paul began to cry. As he told me in 1994, 'When Fela and his band eventually began to play, after a long, crazy build-up, I just couldn't stop weeping with joy. It was a very moving experience.'

Again, though for every Lagos 'up' there seemed to be a 'down'. Having seen Paul at the club, Ransome-Kuti went on Lagos radio claiming that Paul was in the country to exploit and steal African music. He even dropped by the EMI studio one day, accompanied by his entourage, and accused Paul face to face. Paul played him the tracks to assure him that he wasn't using any African musicians or sounds, and that such recordings could have been made anywhere in the world. All the same, Paul felt which way the wind was blowing and opted not to invite any local musicians to play on the album in case it inflamed the situation.

There was also some tension with the drummer Ginger Baker, formerly of Cream, who had left England for Nigeria and set up a recording venue in Ikeia. Baker wanted Paul to record all of his album at his place, ARC Studio; to keep the peace, Paul promised to go there for a day. 'Picasso's Last Words' - a song intentionally fragmented, to reflect Picasso's cubist work - was taped at ARC. Pleasingly, Ginger Baker joined in the fun, playing a percussive tin of gravel on the song.

Eventually, by the third week of September, Wings were more than ready to return to England. Paul and Linda hosted an end-of-album beach barbecue to celebrate and everyone flew back to Gatwick, landing on 23 September - to a greeting from scores of fans and journalists despite the delayed 3am arrival.

Some two weeks after returning to London, Wings went back into the studio to complete the album. Most of this final work was done at George Martin's AIR Studios on Oxford Street (although George himself did not participate). Songs requiring overdubs were transferred from the Lagos eight-track tapes to 16-track. Howie Casey, an old mate of Paul's from Liverpool (Howie Casey and the Seniors were the first Mersey beat band to gain a London recording contract), was brought in to craft sax solos on 'Bluebird' and 'Mrs Vandebilt', thus rekindling a friendship that led to Casey's involvement in all of Wings' subsequent concerts. Wings roadies Ian and Trevor joined in the backing vocals on 'No Words', the only song on Band On The Run not written by Paul and Linda - it was a McCartney-Laine composition, started by Denny and completed by Paul. And then Remi Kabaka came in to overdub percussion on 'Bluebird'. In a neat irony, Kabaka, a former bandmate of Ginger Baker's, turned out to have hailed from Lagos, so a local musician appeared on the album after all.

The most significant work effected at AIR was the recording of 'Jet', and the overdubbing of orchestral parts. Paul invited Tony Visconti to write the arrangements, admiring his production work. (He also happened to be married to Paul's former Apple protégée Mary Hopkin.) Visconti scored the orchestral overdub on 'Band On The Run', strings and saxes on 'Jet', brass and strings on 'No Words', strings on 'Picasso's Last Words', and strings for end of 'Nineteen Hundred And Eighty Five'. (Also during these AIR sessions, Linda recorded 'Oriental Nightfish', eventually released on the album Wide Prairie in 1998.)

After the cover photo was shot on 28 October, Band On The Run was completed with a rapid three-day mix at Kingsway Studios. A month later the album was in the shops. Even more rapidly, 'Helen Wheels', also recorded in Lagos, was rushed out as a single, released in Britain before the end of October.

Despite the rollercoaster Lagos experience, the wish for Wings to work in unusual locale continued to burn within Paul McCartney. Even before the album was out they were recording at EMI's Paris studios (where they taped, among other tracks, Linda's 'Wide Prairie'), Nashville sessions in 1974 led to the 'Junior's Farm' single, much of Venus And Mars was cut in New Orleans, London Town was mostly recorded on a boat moored off the Virgin lslands, 'Mull Of Kintyre' was taped on location in that remote part of Scotland, 'Daytime Nightime Suffering' was recorded in the basement at Paul and Linda's London office, and the band's final album, Back To The Egg, was cut within the draughty walls of Lympne Castle in Kent.

Speaking recently, Paul considered that Band On The Run was the second most enjoyable album he'd made since the Beatles, the first being McCartney. 'It was a challenge to be in Lagos, and very uphill,' he reflected, but Paul McCartney is never one to shirk from a challenge. Miraculously, the album is so assured - buoyant even - the songs are uniformly strong and the vocals and musicianship brim with confidence. Band On The Run went gold in the USA 12 days after release, was voted best album of 1973 by Rolling Stone, was the best-selling album in Britain in 1974, and became the first McCartney album to be issued in the still iron-curtained Soviet Union. At the 1975 Grammy Awards it won two honours, Best Contemporary/PopVocal and, for Geoff Emerick's work, Best Engineered Album.

Despite - or perhaps because of - the litany of trials that surrounded its making, Band On The Run was a glorious accomplishment.

Mark Lewisohn

As his car eased into the grounds of one of London's finest houses, Paul McCartney is unlikely to have realised that he was just five weeks away from releasing his most successful work since the Beatles and probably his best-loved: the Wings album Band On The Run. He also is unlikely to have realised that the finishing touch he was about to apply to this vinyl, cassette and cartridge release would swiftly secure a place in the pantheon of The World's Most Recognisable Pieces Of Cover Art.

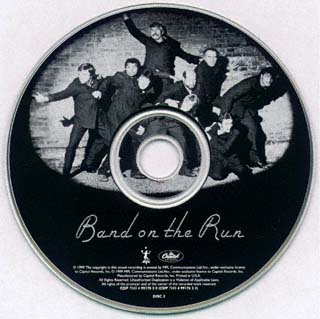

The date was Sunday 28 October 1973. Two days earlier, Wings, mightily productive, had released 'Helen Wheels' as their new single; now they were going to create the sleeve for their second album of the year.The idea for the cover echoed ever so slightly another record with which Mr McCartney was strongly associated: Sgt Pepper. For that sleeve, back in 1967, four real people had posed among cardboard cut-outs and wax effigies that combined to make up a crowd of famous faces. Now, to depict a band on the run, there were nine famous people, in prison uniform, breaking out of jail. About to scale a wall to complete the breakout, however, the escapees are framed in the harsh glare of a guard's searchlight.

Three of these nine comprised Paul, Linda and fellow Wings bandmate Denny Laine, the other six were celebrities certainly recognisable to the British observer, two or three of them known also beyond the UK's shores. Sleeveyvise, left to rightwise, those trying to Run numbered Michael Parkinson (the journalist best known for his Saturday-night TV chat show), Kenny Lynch (the singer, occasional actor and TV wagster), Paul, James Coburn (the American actor - he happened to be in Britain at the time filming The Internecine Project), Linda, Clement Freud (the gourmet, raconteur and wit who went into politics), Christopher Lee (the actor best known for his horror movie roles), Denny Laine, and John Conteh (the boxer from Liverpool who went on to become World Light-Heavyweight champion).

All six celebrities had been summoned to Osterley Park in west London, a mere vapour trail away from Heathrow Airport - where - in the lake-dotted grounds of the 16th-century Osterley House - a brick wall adjacent to a gravel path had been selected as the prime location for the cover photo. One by one the Band wishing to Run arrived from their luncheon rendezvous, to be met not only by the McCartneys' chosen photographer Clive Arrowsmith, but also a film crew under the direction of Barry Chattington, exposing the events on to 16mm.

Handily, or perhaps it wasn't a coincidence, Sunday 28 October was the first day of the 1973 British winter time, Britons having turned back their clocks by one hour just the night before. This meant that the darkness necessary for the session fell quickly, late in the afternoon, shortly after the prisoners-to-be had made their way to a locker room inside Osterley House, where they changed into the garb they would wear for the shoot.

While Linda moved around the room taking Polaroids, Paul chatted comfortably with Conteh and Parkinson, jested with Parkinson's children, who had come along to watch the fun, and prompted a brief 'Misery' duet with Kenny Lynch that turned back the calendar ten years - Lynch had been the first artist to record a cover version of a Beatles song when, in March 1963, he released the Please Please Me track as a single simultaneous with the Fab Four's own version. Linda then grouped together half a dozen of the nine for an informal shot that prompted Paul to joke 'This is the cover. Forget the prison outfits!'

If this easy-going atmosphere conveys a sense of confidence in what was to follow, then it ought not, for it seems that none of the six celebrity invitees knew precisely what was in store for them. So it was on a need-to-know basis that Clement Freud sidled up to Paul and asked him, blankly, 'What do you have in mind?'.

'Prison,' Paul replied, in a single word.

'A mixed prison?'

'No.'

'No women?'

'No. Well, there is one,' Paul responded, pointing to his partner, 'but we're going to have to do her over.'

Suitably 'done over' - her face paled and long-hair tucked under the prison uniform - Linda looked of a kind among the eight males as they took up their positions in front of the brick wall. Clive Arrowsmith ran the show from here on, perched up a ladder and bawling instructions at his famous convicts by way of a megaphone.

'Get those children off the wall.'

'Are they stuck up there?'

'OK, everyone, react as if you've just all been caught by the light.'

'You really must stay very still for that one second, please.'

'Yes, that's good, now FREEZE!'

As one might expect, the perfect shot was not the first to be taken, and a good roll or two of film was exposed so that the best image could be selected later.

Although the light was limited - had Chattington's film crew added extra lighting it would have spoiled Arrowsmith's rig - the wisdom in having the event shot too on to 16mm was proven on the 1975-76 Wings world tour, when what appeared to be the Band On The Run image, back-projected during performances of the song, most effectively began to move.

By this time, record-store tills around the world had long been ringing the sound of success for Wings' third album ... with millions of copies of the sleeve being appreciated alongside the music.

Mark Lewisohn

adapted from an article first published in Club Sandwich #77

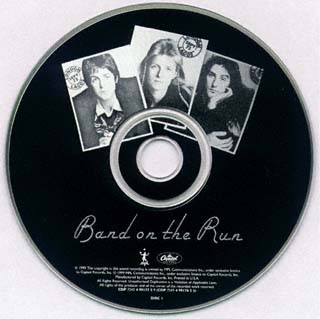

| CD1 Original album produced by Paul McCartney Engineer: Geoff Emerick Sax Solos: Howie Casey Special Thanx to EMI Studios (Lagos and London) and ARC Studio Lagos and Clive Arrowsmith, Tony Visconti, Ian and Trevor, Gordon House and Storm Thorgerson And Paul would like to thank Linda and Linda would love to thank Paul and thanx Denny Re-mastered by Greg Calbi and Geoff Emerick at Sterling Sound All titles published by MPL Communications Ltd. All tracks composed by Paul & Linda McCarmey except tack 7 Paul McCartney & Denny Laine

|

CD2 Produced by Paul McCartney and Eddy Pumer Music Produced by Paul McCartney; Sonic Solutions (Abbey Road Studios); Peter Mew Engineer, Band On The Run (Nicely Toasted Mix), (Strum Bit), (Northern Comic Version) and Helen Wheels (Crazed) Geoff Emerick Engineer, Picasso's Last Words (Drink To Me) (AcousticVersion): Eddie Klein. Special Thanks to lnterviewees: Clive Arrowsmith, James Coburn, John Conteh,Al Coury, Geoff Emerick, Clement Freud, Dustin Hoffman, Denny Laine, Christopher Lee, Kenny Lynch, Michael Parkinson, TonyVisconti. Additional Thanks to Alan Crowder, Alistair Donald, John Hammel, Jamie Kirkham, Eddie Klein, Mark Lewisohn, Mary McCartney, Lou Mann, May Pang, Bill Porricelli, Mike Read, Steve Rosenblatt, Keith Smith. Front Cover, Back Cover and Page 9: photographs by Clive Arrowsmith. All other photographs: Linda McCartney. Mastered by Steve Rooke and Geoff Emerick at Abbey Road Studios All tracks composed by Paul & Linda McCartney except 'NoWords' by Paul McCartney & Denny Laine |

1999 PLUGGED - the unofficial Paul McCartney homepage.